Patients with newly identified vestibular schwannomas (VSs) discuss the optimal management strategy with their care team to create a treatment plan tailored to their specific tumour and circumstances. Observation, stereotactic radiation, and microsurgical resection are the mainstays of treatment for VSs. When tumour size, growth rate, and patient factors such as age and degree of symptoms are appropriate, surgery may be the most suitable option. The modern surgical philosophy for benign disease, such as VS, balances two goals: maximal tumour resection and maintaining functionality of the closely involved cranial nerves.

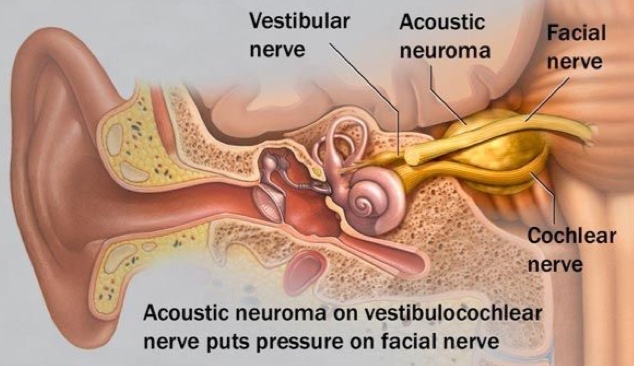

In all cases of VSs, the tumour is in direct contact with the facial nerve. For this reason, facial weakness or paralysis (total lack of facial motion) on the side of the tumour are always risks of surgical resection of VSs. Whether temporary or permanent, facial nerve impairment may have a significant cosmetic, psychological, and functional impact. The association of facial nerve impairment to lower overall quality of life is well-recognized.

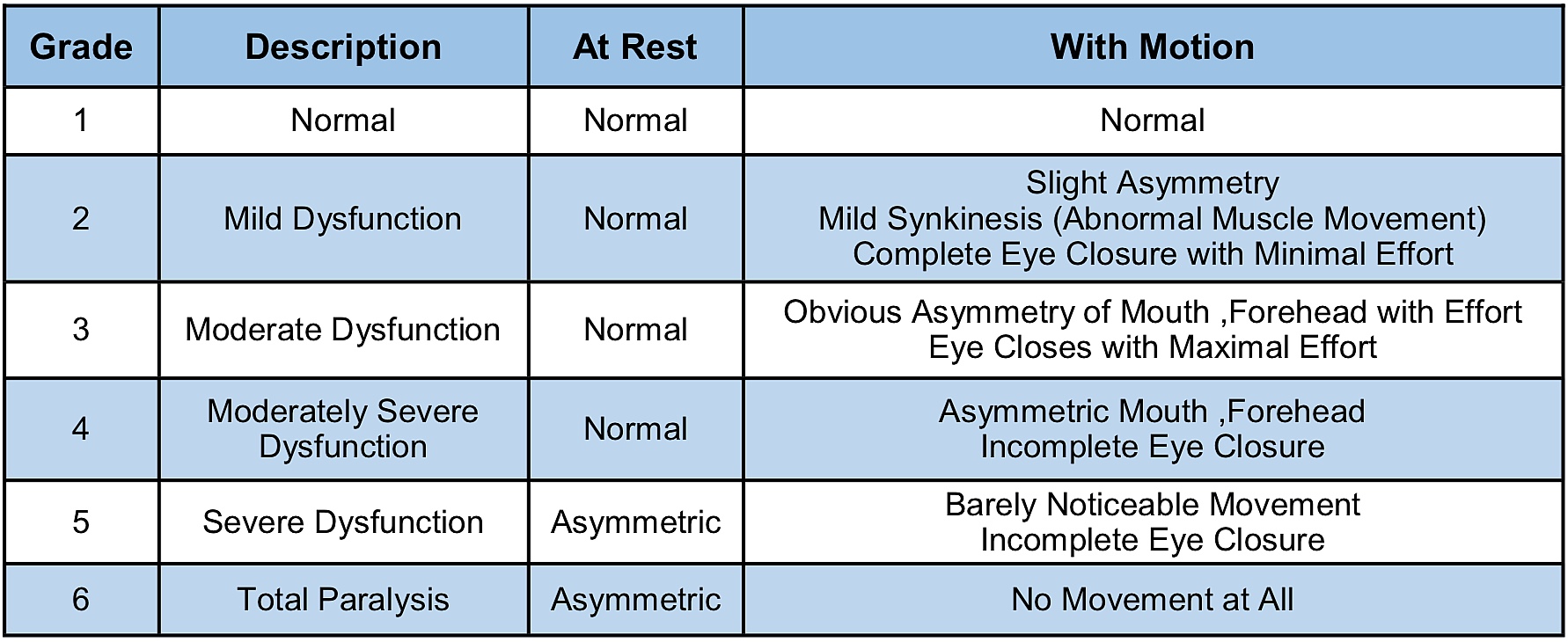

Facial nerve function is most often classified by clinicians using the House-Brackmann (HB) Facial Nerve Grading System. The HB scheme is used to quantify the strength and functional integrity of the facial nerve (Table 1). Reported rates of facial weakness or paralysis following surgical resection for VSs vary, but tumour size, pre-operative facial weakness, and prior radiation therapy are well-known risks factors for facial nerve impairment after surgery. A recent report that pooled data from several different medical centers found that 67% of patients with large VSs (≥2.5 cm) had good facial nerve function (≤HB III) immediately after surgery, and 81% had good function one year after surgery.

In the interest of decreasing the risk of facial nerve impairment associated with surgery for VSs, some surgeons have taken to performing near-total tumour resections rather than a gross-total tumour removal. Gross-total tumour resection implies that all visible tumour tissue is completely removed; near-total tumour resection implies that greater than 95% of the visible tumour is resected but a minute portion of tumour is left behind. A third category of resection is debulking, whereby the tumour volume is reduced, but a substantial proportion of tumour is left in place. In our practice, the goal is gross-total resection whenever possible, but we selectively apply near- total resection when there is elevated concern for risk to the facial nerve.

Concern for facial nerve integrity may be raised during surgery based on a number of indicators. For example, the degree to which the nerve is adherent to the tumour may signify that more aggressive resection could lead to permanent facial nerve impairment. Concern may also be raised by safety monitoring systems that are routinely used in such cases to monitor the nerve. For example, when the facial nerve experiences tension, stress or irritation, an electrophysiologic response can be detected from the facial muscles it controls, which the surgical team can monitor and track during surgery.

There is good evidence that less-than-total tumour resection can lead to superior facial nerve function after surgery. A study by Monfared and colleagues examined the records from a multi- institutional sample of patients with large VSs (≥2.5-cm) to determine the relationship between extent of tumour removal and facial nerve outcomes. They considered two points in time: the first post-surgery appointment and at ≥1-year post-surgery. Superior immediate post-operative facial function was associated with a larger percentage of tumour left behind as demonstrated on follow up magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. Schwartz and colleagues similarly found

significantly higher rates of “good” facial outcomes (considered HB 1 or 2) with less-than-total resections on both early and late follow-up compared to patients who had total-resections. In this study, treatment to ensure eye protection (required when facial weakness is severe enough that the eyelid does not close naturally) was also needed more often with total resections.

An important distinction must be made between near-total resection and debulking. While the judicious use of partial tumour resection appears to be a safe means of preserving functionality of the facial nerve, tumour regrowth is a risk. Rate of tumour recurrence appears to be closely related to the amount of tumour that is left behind, which is greater with debulking relative to near-total resection.

A study by Syed and coinvestigators looked at the records of patients with medium-size VSs who underwent less-than-total tumour resections. They reviewed follow-up MRIs for an average of >5- years to monitor for post-surgery regrowth. Regrowth was seen in 3 of 42 patients overall, all of whom had essentially undergone debulking, rather than a more substantial, near-total resection. Monfared and colleagues also found a three-times higher rate of tumour regrowth in patients who had debulking (28.2% regrowth) versus patients who had near-total (9.1% regrowth) or total resections (8.3% regrowth). A third study of 103 patients found that those who underwent debulking were >13 times more likely to demonstrate regrowth than those who underwent near- total resection. From a residual tumour regrowth standpoint, therefore, there appears to be support for the benefit of near-total resection over any lesser degree of tumour removal.

Following surgery, regardless of the extent of tumour resection, monitoring must be performed for recurrence or progression of disease. This is accomplished with regular follow-up MRIs, at least on an annual basis for the first several years. Most tumours treated in such a fashion do not show further growth, and when they do, regrowth tends to be very slow. If residual tumour growth is detected, this is usually amenable to stereotactic radiation to achieve long-term control. Tumour control success rates using radiation as stand-alone therapy range from 81% to 99%, but tumour control with radiation following partial tumour resection is less well-studied.

A recent publication by Troude and coauthors addressed this question. These investigators looked at a series of VSs treated surgically with less than total resection. Patients were then either simply followed with MRIs over time, or they received radiation early, once healing from surgery was complete. For patients followed with imaging alone, at time points 1-, 5-, and 7-years after surgery, “no-growth” rates were 95%, 82%, and 76%, respectively. For patients that received radiation right after surgery, “no-growth” rates were 99%, 81%, and 78%, respectively. Because the difference in tumour control between these two groups is very small, we advocate for post-operative observation with imaging in cases of near-total resection, reserving radiation if growth is eventually detected.

In summary, the existing data supports the selective use of near-total tumour resection for VSs to best achieve the dual goals of maximal tumour removal and optimal facial nerve function. The greater the amount of residual tumour remaining, however, the higher the likelihood for recurrence. Whenever safely possible, therefore, near-total resection is recommended over lesser degrees of removal or tumour debulking. The extent of resection is typically surgeon-determined based on how the tumour and facial nerve behave during surgery, but patients and their families should be made aware of the concept of total-versus near-total resection versus debulking along with the relative advantages and risks of each scenario. As with all aspects of VS treatment, the patient and their care team should have an in-depth discussion about facial nerve outcomes and strategies, such as selective use of near-total resection in order to be fully informed decision makers.

This article was originally published in ANA Notes.

Michael Harris, MD, who is with the Department of Otolaryngology & Communication Sciences; Division of Otology, Neurotology & Skull Base Surgery completed his fellowship training at The Ohio State University in adult and pediatric otology, neurotology, and cranial base surgery. He has advanced training in surgery for hearing restoration including the placement of cochlear implants (CIs), bone-anchored aids, brainstem implants, and implantable hearing aids. He also has extensive training in the diagnosis and treatment of vestibular disorders and skull base disorders that affect the hearing, facial, and balance nerves.

Nathan T. Zwagerman, MD, who is with Department of Neurosurgery; is assistant Professor and Director, Pituitary and Skull Base Surgery. He joined the faculty at the Medical College of Wisconsin in 2017 after completing his fellowship in endoscopic endonasal pituitary and endoscopic and open skull base surgery at the University of Pittsburgh. His research has been focused on evaluating patient outcomes after endoscopic skull base surgery and developing improved techniques to repair injured peripheral nerves.